By Ajit Krishna Dasa

Link to the original article

This article revisits an earlier analysis of Bhagavad-gītā 12.12 concerning the phrase “regulated principles,” which was later changed to “regulative principles” in post-1977 editions of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books. This change belongs to the broader pattern of Bhagavad-gītā As It Is changes and Srila Prabhupada book changes introduced after his departure.

The original article can be found here:

https://arsaprayoga.com/2016/03/24/regulated-principles-regulated/

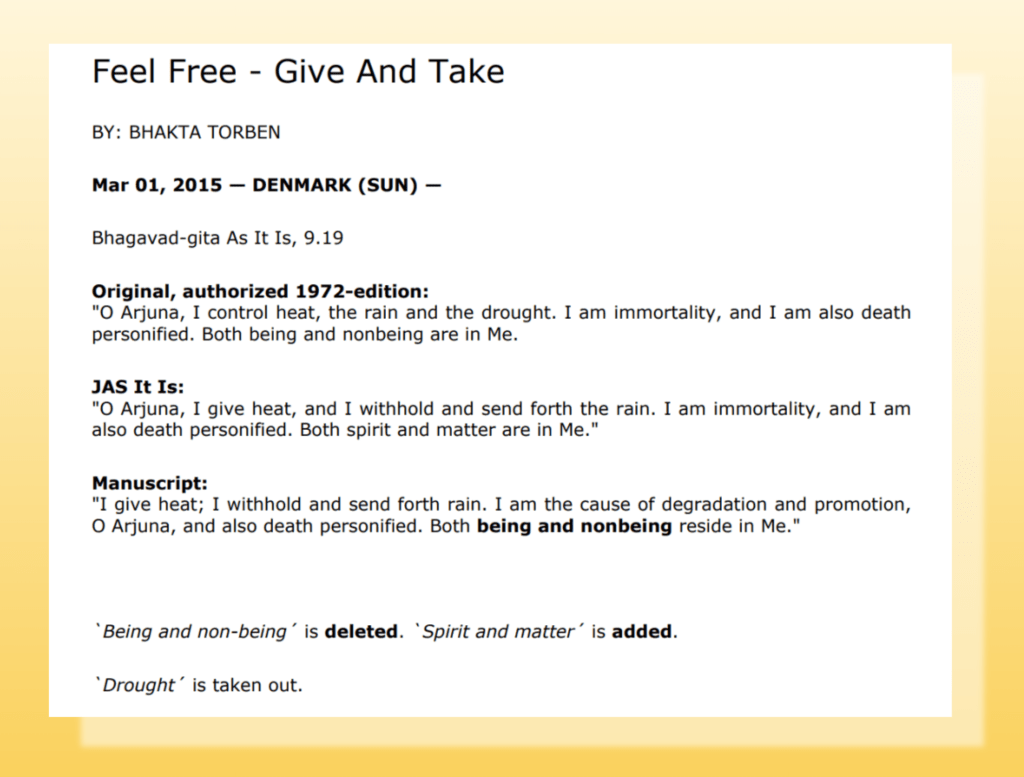

Description of the change

In the original edition of Bhagavad-gītā 12.12, Śrīla Prabhupāda used the phrase “regulated principles.” In later editions, this wording was replaced with “regulative principles,” as part of ongoing BBT editorial changes.

The change was justified by the editor, Jayadvaita Swami, on the grounds that “regulated principles” is “obviously erroneous” and “a term that makes no sense,” whereas “regulative principles” is said to be the “usual and sensible” expression. This justification has frequently been cited in discussions concerning Jayadvaita Swami editing.

The editor further argues that Śrīla Prabhupāda’s earlier instruction not to change the wording of Bhagavad-gītā 12.12 applied only to a specific question about sequence, and should not be extended to prevent later editorial revision of individual words or phrases.

Type of editorial change

Substitution (Replacement)

One expression (“regulated principles”) has been exchanged for another (“regulative principles”).

This substitution is justified through Interpretive Editing, insofar as the editor’s judgment about what “makes sense” and what is “usual” is allowed to override the author’s actual wording.

The change is not based on:

– a typographical error

– a grammatical mistake

– manuscript or draft evidence

– or a request from the author

It is a preference-based replacement.

Category

Posthumous interpretive substitution with systemic normalization

A valid expression used repeatedly by the ācārya was replaced after his departure, not on the basis of error, manuscript evidence, or authorial revision, but through editorial judgment regarding what was considered “sensible” or “correct.”

Although the substitution may appear minor in isolation, it participates in a broader pattern of posthumous normalization, whereby authorial language is silently replaced across the corpus according to later editorial preference. The result is a subtle but real shift in meaning, moving from principles presented as regulated by authority to principles framed as impersonal regulatory norms.

Commentary

Authorial instruction

In a letter dated March 17, 1971, addressed to Jayadvaita Swami, Śrīla Prabhupāda wrote:

“So far changing the wording of verse or purport of 12.12 discussed before, it may remain as it is.”

The statement is clear. Śrīla Prabhupāda refers explicitly to the wording of both the verse and the purport of Bhagavad-gītā 12.12 and instructs that it remain unchanged.

This is the natural and default reading of the sentence. No qualification is stated, and no limitation is expressed.

Jayadvaita Swami suggests that Śrīla Prabhupāda was referring only to a specific editorial issue then under discussion. However, that is a restrictive reinterpretation, not the plain meaning of the text. If only a single, narrowly defined change were being ruled out, there would be no reason to mention both the verse and the purport, nor to speak broadly of “changing the wording.”

Once an author issues a clear instruction to leave the wording of a passage unchanged, the burden of proof lies entirely on anyone who wishes to override that instruction. In this case, no manuscript evidence, authorial clarification, or demonstrable error has been produced that would justify doing so.

The later substitution therefore proceeds not from authorization, but from editorial judgment applied in defiance of an explicit instruction.

Status of the original wording

The editorial justification for replacing “regulated principles” rests on the claim that the phrase is “obviously erroneous” and “a term that makes no sense.” This claim is central to the justification offered in defenses of Srila Prabhupada book changes, since it is presented as grounds for altering the wording of the text.

However, even this line of argument is hypothetical. According to the arsa-prayoga principle, the words chosen by the ācārya are themselves authoritative and are not to be altered on the basis of later judgment, stylistic preference, or perceived improvement. The burden is therefore not merely to allege an error, but to demonstrate one so compelling that it would override both explicit authorial instruction and the governing principle of preserving the ācārya’s language.

No such demonstration has been made.

“Regulated principles” is a grammatically normal adjective–noun construction in English, denoting principles whose application or scope is regulated by authority. The expression is widely attested in formal English usage, particularly in legal, academic, and institutional contexts. It is neither novel nor idiosyncratic.

A phrase that is both grammatically correct and semantically intelligible cannot be classified as an error. At most, it may be considered less common than an alternative. But uncommon usage is not the same as incorrect usage, and editorial preference does not convert a valid expression into a mistake.

Since the original wording is not erroneous, the justification collapses even on its own terms. And even if an error were alleged, it would still fail to meet the standard required to override arsa-prayoga and a clear authorial directive.

The substitution therefore represents not a correction, but an editorial judgment imposed after the fact.

Śrīla Prabhupāda’s own usage

The claim that “regulated principles” represents an error is further undermined by Śrīla Prabhupāda’s own consistent usage of the term.

Śrīla Prabhupāda employed both expressions—“regulative principles” and “regulated principles”—throughout his preaching and teaching life. He used them before coming to the West and continued to use them afterward. The expressions appear across multiple genres: books, letters, lectures, and recorded conversations.

While “regulative principles” is more frequent, frequency alone is not evidence of correctness, nor does it establish exclusivity. Authors routinely employ a dominant term alongside contextual variants, especially when addressing different aspects of a subject.

Notably, Śrīla Prabhupāda tends to use “regulated principles” in contexts where emphasis is placed on regulation by authority—that is, principles as administered, defined, or enforced by the spiritual master or governing discipline. In such contexts, the term functions descriptively rather than categorically.

This pattern of usage indicates deliberate expression, not linguistic confusion. It also rules out the suggestion that the phrase was an accidental or unconscious deviation from a supposedly correct form.

Under the arsa-prayoga principle, such usage carries decisive weight. The language employed by the ācārya—especially when repeated across time and context—constitutes authoritative usage and is not subject to retroactive normalization based on later editorial preference.

The nature of the editorial justification

The substitution of “regulated principles” with “regulative principles” is justified not by manuscript evidence, not by authorial revision, and not by demonstrable error, but by an editorial assertion: that the original wording “makes no sense.”

This form of justification is significant. It does not appeal to facts about the text, but to an editor’s judgment about what ought to make sense, what is “usual,” and what is considered acceptable terminology. In doing so, it quietly shifts the basis of authority from the author’s expressed language to the editor’s linguistic intuition.

Such a move reverses the proper order of editorial responsibility. Editors are entrusted with preserving an author’s words, not with revising them according to later standards of clarity, convention, or taste—especially when the author has explicitly intervened and instructed that the wording remain unchanged.

Moreover, the claim that a phrase “makes no sense” is not a neutral observation. It is an evaluative judgment that demands substantiation. In this case, no such substantiation is provided. The phrase in question is grammatically sound, semantically intelligible, and demonstrably used by the author himself and by competent writers outside this tradition.

The justification therefore rests on an unargued assertion presented as self-evident. When such assertions are allowed to function as grounds for textual alteration, editorial judgment replaces authorial intent as the final arbiter of meaning.

Under the arsa-prayoga principle, this is precisely the point at which editing ceases to be custodial and becomes interpretive. The substitution is not driven by necessity, but by preference—expressed in the language of inevitability.

Implications of the “nonsense” claim

The claim that “regulated principles” is a term that “makes no sense” carries implications far beyond Bhagavad-gītā 12.12.

If the expression were genuinely nonsensical or erroneous, consistency would require that it be corrected wherever it appears. In practice, this is precisely what has occurred. In the edited corpus published by the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International (BBTI), the expression “regulated principles” has been systematically replaced with “regulative principles.” Searches for the former term in BBTI’s website vedabase.io now lead only to the latter.

This means that the issue is no longer confined to a single verse or purport. The original expression has effectively been removed from Śrīla Prabhupāda’s published works, despite the fact that it is grammatically valid, semantically clear, and demonstrably used by him across books, letters, lectures, and conversations.

The implications are therefore substantial. Accepting the claim that the term “makes no sense” entails the conclusion that Śrīla Prabhupāda repeatedly employed nonsensical language throughout his preaching and teaching life, and that this language required silent correction after his departure. This conclusion is untenable.

Once it is acknowledged that the phrase is valid English and contextually meaningful, the premise underlying its systematic removal collapses. What remains is not correction of error, but posthumous normalization imposed according to editorial preference.

This case therefore illustrates how a single unsubstantiated linguistic judgment, once accepted, can justify wide-ranging alteration of an ācārya’s language across an entire corpus.

Philosophical impact

Although the substitution may appear minor, it is not without interpretive consequence.

The phrase “regulated principles” presents the principles in question as having been regulated—that is, as defined, delimited, and enforced by authority. The emphasis falls on regulation as an act: principles are regulated by someone, within a specific disciplic and administrative context. The formulation naturally directs attention toward the role of the spiritual master and the concrete transmission of discipline.

By contrast, “regulative principles” frames the same practices as a class of principles whose function is to regulate behavior in general. The emphasis shifts from regulation by authority to regulation as an abstract characteristic. The principles are presented less as imposed disciplines and more as impersonal normative categories.

Both expressions can coexist within Vaiṣṇava teaching, and both are doctrinally compatible. The issue is not theological contradiction, but framing. Language does not merely convey rules; it frames how authority, obligation, and transmission are understood.

In this case, the substitution subtly moves the reader’s attention away from regulated practice as something received through authority and toward regulated practice as something conceptually defined. The result is a small but real shift from personal administration to impersonal classification.

Under the arsa-prayoga principle, such shifts matter. The language chosen by the ācārya is part of the teaching itself, not a neutral vehicle that may be freely exchanged for a preferred equivalent. When authorial wording is replaced on the grounds of editorial sense-making, even slight changes accumulate and alter how discipline and authority are perceived.

The significance of this case, therefore, does not lie in the gravity of the substitution taken in isolation, but in the precedent it sets: that an editor’s judgment about clarity may override the ācārya’s chosen language, even where that language is valid, intentional, and explicitly protected from alteration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.