Śrīla Prabhupāda on Unauthorized Editing and Post-Samādhi Changes

By Ajit Krishna Dasa

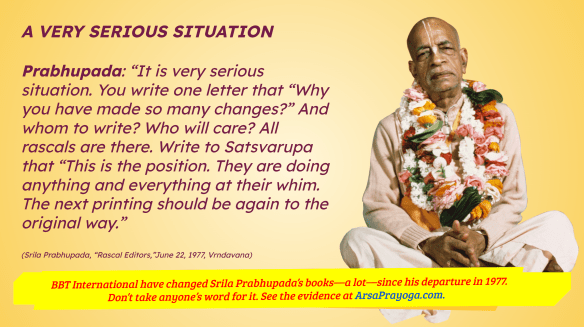

Discussions about post-samādhi editing of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books often assume that the real problem began after 1977. But Śrīla Prabhupāda himself tells a different story. In the well-known “Rascal Editors” conversation dated June 22, 1977, in Vṛndāvana, he describes a situation already unfolding — one marked by unauthorized editing, loss of control, lack of accountability, and the impossibility of verification.

Far from being historically irrelevant, these remarks reveal a structural problem — one that makes post-samādhi editing not only questionable, but fundamentally illegitimate.

Editing Without Control — Already in 1977

Śrīla Prabhupāda states:

“It is starting. What can I do? […] They make changes, such changes… So how to check this? How to stop this?”

This is a critical admission. Prabhupāda is not predicting a future danger; he is describing a present reality. Editorial changes were already occurring, and he openly acknowledges that he lacks the practical ability to stop them.

This point alone carries enormous weight. If the author himself — alive, present, accessible, and formally in charge — could not effectively control editorial activity, then any claim that editorial control somehow improved after his departure is untenable. The conditions for restraint were already weakening; after samādhi, they could only deteriorate further.

The Defining Issue: Absence of Authority

Prabhupāda continues:

“…they are doing without any authority […] Very serious feature.”

Here the issue is precisely identified. The problem is not accidental error, linguistic awkwardness, or the need for stylistic polish. The problem is unauthorized action.

This distinction is crucial when discussing posthumous changes to Prabhupāda’s books. Appeals to “clarification,” “restoration,” or “philosophical consistency” are irrelevant if no authority exists to sanction such changes. In a Vaiṣṇava framework — especially under the principle of ārṣa-prayoga — authority does not arise from competence, intention, or institutional position. It must be explicitly granted.

Without authority, even a well-intended edit is illegitimate.

“Jayadvaita Is Good” — A Misused Argument

At this point, defenders of post-samādhi editing often introduce the following exchange:

Tamāla Kṛṣṇa: Your original work that you’re doing now, that is edited by Jayadvaita. That’s the first editing.

Prabhupāda: He is good.

Tamāla Kṛṣṇa: He is good. But then, after they print the books, they’re going over. So when they reprint…

Prabhupāda: So how to check this? How to stop this?

Tamāla Kṛṣṇa: They should not make any changes without consulting Jayadvaita.

From this, it is claimed that later editorial changes are justified because Jayadvaita Swami was trusted by Śrīla Prabhupāda.

This argument fails on several levels.

First, Prabhupāda’s approval of Jayadvaita was contextual and temporal. He approved Jayadvaita’s editing at that time, under his supervision, and within a defined scope. Nothing in this exchange grants blanket, indefinite, post-samādhi editorial authority.

Second, Prabhupāda himself explicitly rejected the idea that past approval guarantees present legitimacy. He repeatedly warned against exactly this kind of reasoning.

Śrīla Prabhupāda explains the logical fallacy involved:

“This is nagna-mātṛkā-nyāya. We change according to the circumstances. You cannot say that this must remain like this.”

(Morning Walk, May 5, 1973, Los Angeles)

In Nyāya logic, this fallacy assumes that because something was valid in the past, it must retain the same status indefinitely — regardless of changed circumstances. Prabhupāda explicitly rejected this mode of reasoning.

Trust Is Conditional — and Can Be Violated

Prabhupāda further clarifies that trust is never unconditional:

“I have given you charge… but you can misuse at any moment, because you have got independence. At that time your position is different.”

(Morning Walk, June 3, 1976, Los Angeles)

And he states even more plainly:

“Phalena paricīyate […] Present consideration is the judgement.”

(Morning Walk, October 8, 1972, Berkeley)

In other words, a person must be evaluated by present actions, not past reputation. Previous trust does not immunize later conduct.

This principle applies directly here. Whatever confidence Prabhupāda had in Jayadvaita’s editing during his presence cannot be mechanically transferred to a radically different situation: post-samādhi editing, without authorial oversight, involving substantive changes to published works.

Evidence of Breach: Changes in Style, Mood, and Philosophy

This is not a theoretical concern. Post-samādhi editions exhibit clear and documentable changes that go far beyond spelling or grammar. These include alterations to:

- Śrīla Prabhupāda’s personally typewritten Sanskrit translations

- Śrīla Prabhupāda’s spoken, forceful, non-academic style

- the mood and devotional tone of passages

- the philosophical framing and emphasis

- the balance between direct instruction and interpretive explanation

- and, in some cases, the theological perspective itself

Style, tone, and mood are not cosmetic. They are integral to meaning and pedagogy. To alter them without authority is to alter the work — and doing so after the author’s departure violates the trust placed in any editor.

Original manuscripts, first editions, and contemporaneous recordings therefore function only as witnesses to what Śrīla Prabhupāda authorized and published — not as licenses to revise his words post-samādhi.

Then and Now: Structural Parallels

The situation Prabhupāda describes in 1977 and the situation surrounding post-samādhi editing share the same defining features:

- Editorial changes occurring without explicit authorization

- Inability to verify or supervise those changes

- Absence of a final, corrective authority

- Institutional normalization of editorial discretion

- Appeals to past trust rather than present evidence

The difference is not one of kind, but of degree. What was beginning in 1977 became entrenched after Prabhupāda’s departure.

The Unavoidable Conclusion

Śrīla Prabhupāda’s own words establish the following facts:

- Unauthorized editing was already occurring during his presence.

- He could not effectively stop it.

- He could not reliably check or verify it.

- He explicitly warned against relying on past trust as permanent validation.

From this, the conclusion follows with clarity:

Post-samādhi editing of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books lacks authority, lacks verification, and reproduces precisely the dangers he himself identified.

That Jayadvaita Swami was trusted then does not settle the question now. Trust is conditional, circumstances change, and actions must be judged in the present.

Where authority is absent and trust has been objectively violated, restraint is not extremism — it is fidelity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.