By Ajit Krishna Dasa

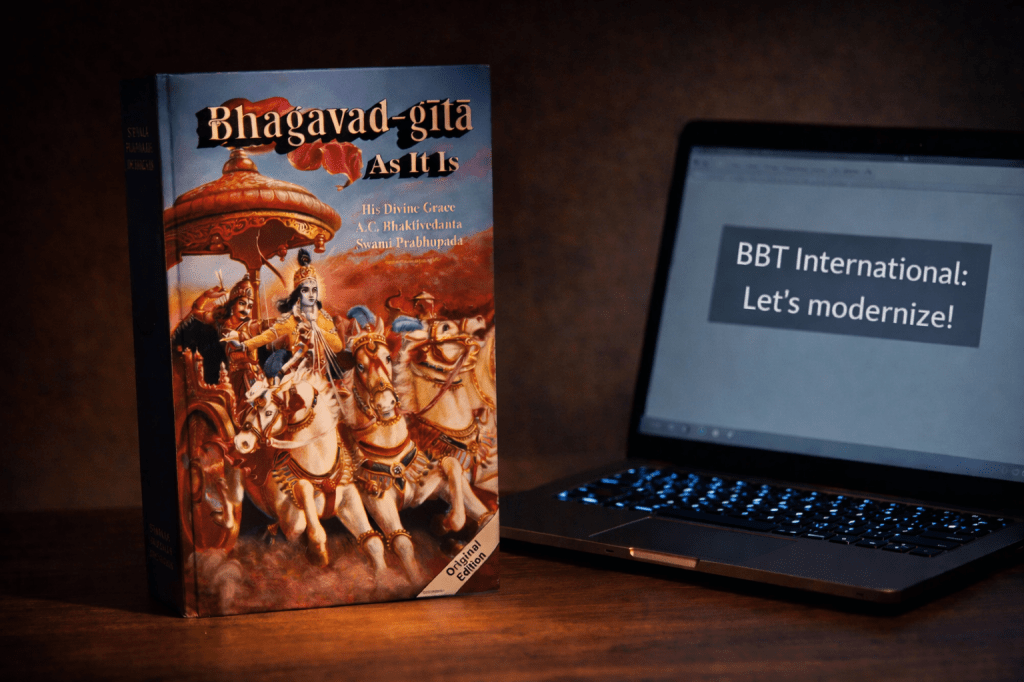

It is often said: “Whatever BBT International is doing will eventually have to happen anyway. Language changes. English will evolve. Therefore, updating Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books is inevitable.”

This argument might sound reasonable on the surface. But when examined carefully, it collapses.

Yes, language changes. That is not controversial. The real question is not whether English evolves. The real question is this:

How does a serious tradition preserve the final, authorized words of its ācārya while also making them accessible to future generations?

Those are two different concerns. And they must not be confused.

First Principle: Authorial Finality

When an author publishes a final edition of his work, that edition becomes historically fixed. This is not sentimentality; it is basic literary integrity. We do not revise Shakespeare because English changed. We do not modernize Dostoevsky by altering his Russian text. We do not update Plato’s Greek.

Instead, we preserve the original and produce new translations or explanatory editions when necessary.

The typically used Bible analogy actually proves this point. When Christians “update” the Bible, they are not editing the Greek manuscripts. They produce new translations. The King James Version still exists. The Greek New Testament still exists. No one retroactively edits them.

Preservation and translation are not the same thing.

Second Principle: The Location of Authority

If posthumous revision becomes acceptable, something subtle but serious occurs. Authority shifts.

It is no longer simply “Śrīla Prabhupāda said.” It becomes, “Śrīla Prabhupāda said — as adjusted by later editors.”

Even if intentions are sincere, the epistemic center moves from the ācārya to the editorial board.

That shift is not linguistic. It is structural.

Third Principle: The Alleged Problem of “Archaic English”

Let us be honest. Śrīla Prabhupāda’s English is not archaic. It is mid-20th century English with Sanskrit terminology. It is often clearer than modern academic theology.

The claim that future generations will need a “course in archaic English” is exaggerated rhetoric. People read Shakespeare in school. They read classical literature. They learn terms. Human beings are capable of intellectual effort.

Accessibility does not require alteration.

Fourth Principle: The Real Solution

If, at some distant point, English changes so radically that comprehension becomes genuinely difficult, the solution is straightforward and principled:

Produce a clearly labeled contemporary English rendering.

For example:

Bhagavad-gītā As It Is – Original Authorized Edition

Bhagavad-gītā As It Is – Contemporary English Rendering

Two distinct works. Transparent. No confusion. No silent revision. The original remains intact and available. The rendering serves as an aid, not a replacement.

This is exactly how translation into any other language works. We do not rewrite the Sanskrit. We translate it. The same logic applies here.

A Tradition That Preserves

Strong traditions preserve their sources. They do not continuously re-edit them according to the sensibilities of later generations.

Language change is inevitable. Editorial authority is not.

The real issue is not readability. The real issue is whether we maintain textual integrity and the clear, final authority of the ācārya.

If the movement flourishes, Śrīla Prabhupāda’s English may itself become devotional standard language, much like older Biblical English still shapes Christian liturgy today.

Language may evolve. But reverence, integrity, and discipline must remain.

And that is the standard by which this issue should be judged.

You must be logged in to post a comment.